Our history

Raqqa

City

Raqqa lies at the confluence of the Euphrates and the Balikh River, a tributary flowing from the north. The earliest settlement in the area dates back to prehistoric times: Tall Zaidan, situated east of the modern city, which existed from the 6th to the 4th millennium BC. This archaeological site revealed layers from the Halaf culture (6000-5000 BC) and the Chalcolithic Ubaid culture (5000-4000 BC).

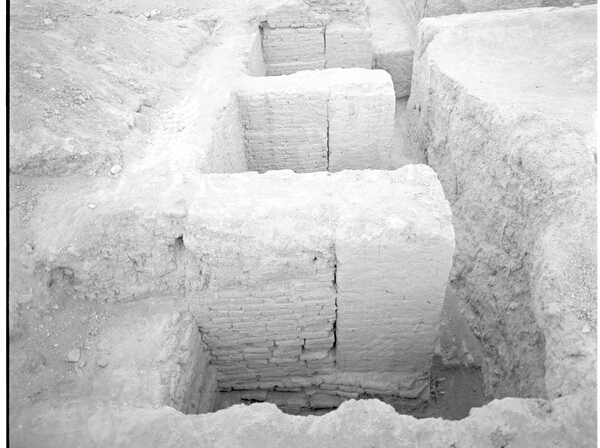

Tuttul / Tall Bi’a

In ancient times, the eastern city of Tuttul, now known as Tall Bi’a, became an important crossroads for trade routes between Aleppo (and the Mediterranean) to the west, Mari to the east, Qatna (near Homs) to the southwest and the Balikh Valley to the north.

A large city wall, palaces, a vast settlement and probably even a port connected with the Euphrates testify to this thriving period in the 3rd and the first half of the 2nd millennium BC.

Tuttul belonged to the kingdom of Mari.

By the early 6th century AD, at least two Christian monasteries existed in Raqqa, one of which was located on Tall Bi’a: Dair Zakka. Archaeological excavations revealed a vast monastic complex of around 2,500 m², with mosaics in some rooms. Two of these mosaics are even dated: the years 509 and 595. They continue to be preserved in the museum's collections.

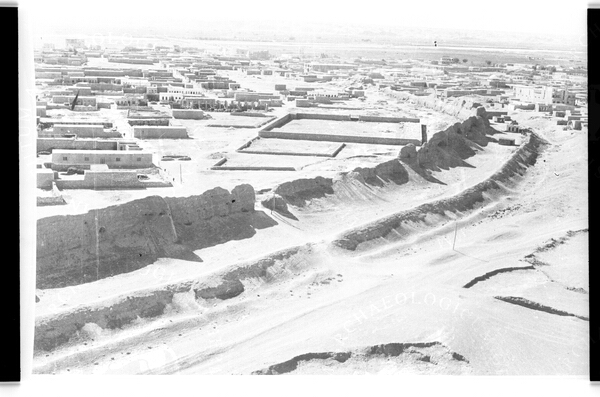

Ar-Raqqa, City Wall of ar-Rafiga (1985, Peter Grunwald)

City wall of ar-Rafiqa, the wall core dates back to the Abbasid period, the partially reconstructed brick facings were carried out as part of restoration project by the Syrian Antiquities Administration between 1976 and 1983.

Baghdad Gate (2024, Baptiste Violi)

Kallinikos, Leontupolis, Nikephorion

In Hellenistic times, around 300 BC, a new city was built south of Tall Bi’a and called Nikephorion ("The Victorious“) in modern day Mishlab. Until the Islamic conquest, Raqqa primarily belonged to the Byzantine Empire, although it was also under Sasanian rule; fortified by a great city wall with towers. Throughout its history, Raqqa changed names several times depending on the rulers. In Greek and Latin sources it was referred to as Kallinikos, Leontupolis, perhaps even Konstanteia, and Nikephorion.

Ar-Raqqa

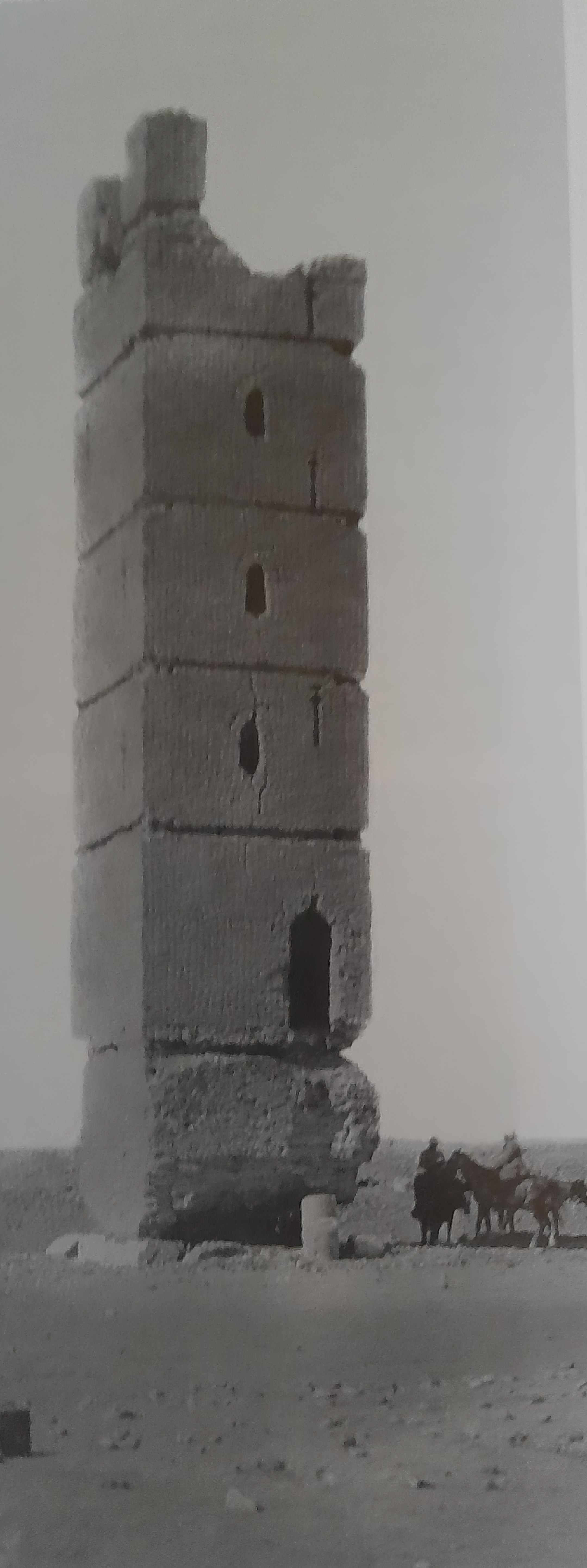

In the year 636- 637, Kallinikos was conquered by Arab troops and then again in 639. The city was renamed ar-Raqqa. In its centre was the large Friday mosque (The Umayyad Mosque) featuring a square minaret that remained standing until the early 20th century, as evidenced by photographs taken by scholars and travelers. The mosque itself was constructed, at least in part, using ancient capitals and columns, some of which were later repurposed as gravestones in the cemetery around the Mausoleum of Uwais al-Qarani. Although the mosque itself is long gone, its irregular outline has since been preserved in the courtyard of a secondary school.

Minaret of the Mosque of ar-Raqqa/Kallinikos (Max von Oppenheim, 1913)

Ar-Rafiqa, aerial photography by Marwan Musselmany and Ahmed Kurumli from 1961, reproduction (1988, Mohammad ar-Roumi)

Ar-Rafiqa

Finally, in 771 - 772, the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur ordered the establishment of a new garrison town to the west of ar-Raqqa, named ar-Rafiqa, “the companion of ar-Raqqa”. However, this name apparently did not take hold as shortly after the twin city became known as "the two Raqqas“, until at last only ar-Raqqa remained. Eventually, it became the largest urban unit apart from Baghdad, even surpassing Damascus.

The ar-Rafiqa wall, shaped like a horseshoe and measuring a total length of 4.5 km, is a defining feature of the city. It had a rectangular grid of streets with the Friday Mosque (The Great Mosque) at its centre. The caliph's palace and his representatives were likely situated nearby, but no architectural traces have been found to date. An implicit hint might be the large quantities of high-quality ceramics of the so-called Raqqa-ware which have been confiscated or sold as a result of illegal excavations since the end of the 19th century.

25 years later, the most famous of all Abbasid caliphs, Harun ar-Rashid, made Raqqa his new residence and moved his capital from Baghdad to the west to better combat the Byzantine Empire. This resulted in the move of the entire court and in the construction of an enormous palace covering approximately 10 ha north and northeast of the twin-city. Around 20 large building complexes have been identified and some of which have undergone archaeological examination.

Luckily, the whole area was documented several times in aerial photos - the first as early as 1924 - where buildings, canals, streets and even a racecourse for horses could be identified. On the ground, it is extremely difficult to discern the walls from the surrounding soil due to the poor preservation of the simple mudbrick walls.

The water supply for this area was secured by two canals coming from the north and the west. The Nahr an-Nil brought water from west of Hiraqla, while the northern canal originated in the Balikh Valley. All the larger palaces had their own water connections to the canals.

The wealth of Raqqa at that time resulted not only from agriculture - Raqqa was famous for its olive trees and vine - but also for its excellent soap and its slave market, where as many as 6,000 slaves could be sold. Among them was even the Bishop of Cyprus who brought 2.000 dinar! From later historical texts we know that in the very fertile Balikh Valley, mulberry trees were grown to facilitate the rearing of silkworms and the production of silk. Apart from that, Raqqa also boasted a significant inland port, but its location is unknown and has yet to be found.

Decline and Bedouin domination

For some decades Raqqa remained an important garrison town under an Abbasid governor, however by the end of the 9th century, the troubles plaguing the Abbasid Empire began to affect the city as well. This resulted in economic difficulties and the population decreased followed by a gradual diminishment of the urban area.

Under Hamdanid rule, Raqqa and the Djazira were ruthlessly exploited which led to further decline. At the beginning of the 10th century, Bedouin tribes from the Arabian Peninsula reached the Djazira and established local nomadic dominions. Thus, 100 years later Raqqa came under Numairid control. They had no “urban” ambitions, although there is archaeological evidence of some restorations in the Great Mosque, which were quickly abandoned.

The situation improved under the rule of the Zangids of Qal’at Gabar, in the 2nd half of the 11th century when agriculture and trade recovered, resulting in new building or restoration projects. This era saw the construction of the Qasr al-Banat, the Baghdad Gate, and the minaret of the Great Mosque. The ancient tradition of pottery was revived and the "Raqqa Ware" became an international bestseller!

After the Mongol invasion, Raqqa and the whole area was devastated and deserted for centuries. From the 16th century, Raqqa became a small Ottoman settlement with a harbour. Later sources even speak of a “beautiful” and an “old castle”, possibly the Qasr al-Banat. The following centuries were marked by the permanent conflict between nomads and Ottoman government.

Qasr al-Banat (2024, Baptiste Violi)

View of Raqqa from the South Banks of the Euphrates (after F.R. Chesney)

Modern History: 19th and early 20th century

After a military expedition in September and November 1864, the Euphrates Valley was once again under Ottoman rule and a military outpost was installed in the southwest corner of the city wall. It was likely during this time that the Saray, predecessor of the current museum, was built. Around the turn of the century the inhabitants of the small settlement relied on trade with Bedouins, the cultivation of liquorice (between Tall Zaidan and Raqqa) and illicit trade of antiques.

Shortly before World War I about 300 families lived here, mainly to the west of the city wall. The village had a mosque, a small suq, a café, mail and telegraph, the military post and a branch of a liquorice factory. In the post-war confusion, the notability of Raqqa, together with ambitious Bedouin sheikhs declared the city's independence and the established atate of its own. After more than a year of complicated negotiations and military actions, the conflict ended with an agreement on the borderlines and Raqqa came under French mandate.

Many improvements were made to the city including the replacement of the old Euphrates River ferries with the construction of an iron bridge, carried out by British military in 1942. The access to the city became easier and quicker which improved infrastructure and trade. Finally, on April 17th 1946, Syria became independent.

Scientific work in and on Raqqa

The Islamic city has been the subject of scientific studies since the 1940s, following visits from researchers such as Gertrude Bell, Friedrich Sarre, and Ernst Herzfeld, who documented its monuments, including the Great Mosque, the Qasr al-Banat, the Baghdad Gate, the minaret of the Umayyad Mosque in Mishlab, and the city wall. However, they all overlooked the extensive ruins located outside the city, likely due to their poor preservation. In 1944, the young Nasib Saliby from the Syrian Antiquities Department was tasked with excavating promising areas of the palace zone after evaluating aerial photographs.

The Syrian Antiquities Department (DGAM) continued work at various places inside and outside the quickly growing town. The “Raqqa specialists,” Nasib Saliby and Kassem Toueir researched Palaces A, B and C, the Great Mosque, the Qasr al-Banat and the City Wall until the 1960s. Its commitment to restoring the city wall won the Raqqa Department of Antiquities international recognition.

To the west of the town, Kassem Toueir examined the impressive ruins of Hiraqla and documented the findings in several scientific publications.

From 1980-1995, the German Oriental Society (DOG) conducted excavations at Tall Bi’a, led by Eva Strommenger. The results of this investigation are published in several large volumes.

From 1981-1994, the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) in Damascus continued the excavations of the early Islamic period in the Palace area. In cooperation with the local Antiquities Department, the cistern of the Great Mosque and the Northern Gate of the city wall were excavated and a comprehensive survey of the remaining sections of the wall was conducted.

In the 1990s, a British team from the University of Sheffield, under Julian Henderson, researched the early Islamic industrial area “between the two Raqqas," where pottery and glass were produced, namely at Tall Fuhhar and Tall Zugag.